I first heard about the concept of black tax when I read Trevor Noah’s book Born A Crime. Trevor explains how his mother did not want him to feel obligated to assist her financially; instead, she wanted him to build his future. Of course, I have experienced black tax in my life but it did not have that label. I was, therefore, intrigued when I learnt that Niq Mhlongo had edited a collection of essays aptly called Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu? With a stellar group of 26 black South African writers giving their opinions on black tax, this book is bound to be a revelation.

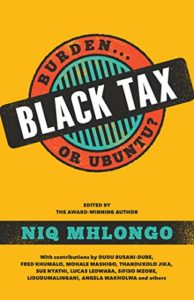

Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu? Was published in 2019. The editor, Niq Mhlongo is an award-winning author of the books such as Dog Eat Dog, Way Back Home, Soweto Under The Apricot Tree and others. He states that it took five months to put the project together, and it was important to compile diverse voices— young and old, urban and rural, male and female. From reading the book, most of the writers struggle to define black tax because of its complexity. For most of the writers, the description of experiences and what it represents is perhaps the best way to explain it. According to Dudu Busani-Dube, “Black tax is opting to go for a diploma when you qualify for a degree, because a diploma takes only three years, and hopefully you’ll get a job after that and take over paying your siblings’ school fees so that your mother can maybe quit her job at that horrible family she is working for in the suburbs.”

Some of the older writers have not welcomed the term black tax as it is wrapped in negative connotations; instead some have suggested it is rebranded to family upliftment, non-fulfilment tax, or collective family responsibility. Regardless, what the writers choose to call it black tax is something that they have benefited from, have participated in or both. There is a sense of obligation that each feels that they need to give back to their family, both nuclear and extended. It is also seen as an extension of African culture. For example, in Fred Khumalo’s essay, he narrates how relatives contributed money for him to attend tertiary education when the time came. He says, “My father explained that I was not supposed to pay the money back as it was not a loan, all that was expected of me was, once I had finished my studies, to extend help to those who need it- to members of my immediate and extended family.”

Almost every essay agrees that black tax results from the legacy of colonisation and apartheid. The fertile land and livestock were taken from the black South Africans. This forced them to work for meagre wages in the mines and share their earnings with families back home. The lack of land and livestock did not offer black South Africans an opportunity to create generational wealth like their white counterparts. Extrapolating this explanation to the broader African continent, colonisation, the HIV pandemic, Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), corruption, and other vices can be blamed for the perpetuation of black tax. In the 2000s, Zimbabwe attempted to rectify the land issue with land reforms bringing about mixed results.

The dilemma with black tax is balancing helping family and ensuring that you free the next generation from the stranglehold of black tax. It is choosing between renovating your parents’ house or investing the money in stocks. It is embedded in the culture, and for anyone to break free, there is a risk of being ostracised by the family. It also creates expectations for those employed to assist the less fortunate. Black tax leads to emotional stress for many and dreams neglected or unfulfilled. One of the most vulnerable and open pieces in this collection is from Thabiso Mafokeng’s essay titled, I must soldier on. In the essay, Thabiso shares the emotional turmoil he endured in trying to support his family. He writes, “My family depended on me financially and emotionally, but I was dying inside. What killed me even more is that I couldn’t tell them, particularly my mother, that I needed a break.”

Even though the essays in Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu? are written from a South African perspective, as a Zambian reading the book, I was able to see myself in many of the stories. I have either experienced them or know someone who has gone through something similar. It is expected that with 26 essays, some will resonate more than others. A few pieces fell flat in terms of writing quality and an exploration of the topic. It could also feel like some essays were repetitions because the writers used similar examples, such as putting siblings through school or building the parents a house. Nonetheless, this is a timely book that shows that black tax is a delicate subject matter, and views will be shaped by personal experience with it. Some have suggested that we cannot dismiss the ubuntu spirit, and others have claimed that boundaries must be drawn if generations are to create new legacies. This book is worth the read, and your perception of black tax will not be the same.

Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu?

162 pages

Publisher: Jonathan Ball

Available on Amazon

Recent Comments